High-Dose Corticosteroids May Undermine Immunotherapy Success in Lung Cancer Patients

High-dose corticosteroids can reduce the effectiveness of immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Doctors often use corticosteroids to help manage symptoms, but these medications may also put patients at risk during treatment. Studies show that corticosteroids can stop T-cells from maturing and make it harder to track cancer using biomarkers. In one patient group, 57% of those on steroids received high doses during immunotherapy.

Patient Group | Number of Patients | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

NSCLC patients on baseline steroids | 21 | 8% (of total cohort) |

Patients on medium-dose steroids | 9 | 43% (of steroid users) |

Patients on high-dose steroids | 12 | 57% (of steroid users) |

Researchers continue to study the link between corticosteroids and immunotherapy in lung cancer to understand how and why these drugs impact treatment success.

Key Takeaways

High-dose corticosteroids can weaken the immune system and reduce the success of immunotherapy in lung cancer patients.

Using high doses of steroids during immunotherapy lowers the chance that tumors will shrink and shortens patient survival.

Corticosteroids interfere with T-cell development, which is essential for the immune system to attack cancer effectively.

Steroids can change biomarker levels, making it harder for doctors to track cancer and adjust treatments accurately.

Doctors should personalize steroid use, balancing symptom relief with treatment risks, and consider safer alternatives when possible.

Corticosteroids and Immunotherapy in Lung Cancer

Why Corticosteroids Are Used

Doctors often prescribe corticosteroids to help lung cancer patients manage difficult symptoms. These medications can quickly reduce inflammation and provide relief. In the context of corticosteroids and immunotherapy in lung cancer, symptom control remains a top priority for patient comfort and quality of life.

The most common symptoms managed with corticosteroids include:

Fatigue

Insomnia

Cough and sputum

Appetite loss

Hypodipsia (reduced thirst)

Pain

Spinal cord compression symptoms

Immune-related adverse events caused by immunotherapy

Corticosteroids and immunotherapy in lung cancer often intersect when patients experience side effects from treatment. While corticosteroids can improve daily living, their use requires careful consideration during immunotherapy.

How Immunotherapy Works

Immunotherapy has changed the way doctors treat non-small cell lung cancer. The most common type, called immune checkpoint inhibitors, helps the body’s immune system find and attack cancer cells. These drugs work by reactivating special immune cells known as CD8+ T cells inside the tumor. Normally, cancer cells send signals that stop these T cells from working. Immune checkpoint inhibitors block those signals, allowing T cells to recognize and destroy cancer cells.

The effectiveness of immunotherapy depends on several factors. These include how many CD8+ T cells are present in the tumor, the level of certain proteins like PD-L1 on cancer cells, and the overall environment around the tumor. Sometimes, other cells in the tumor can make it harder for immunotherapy to work. Doctors must consider all these factors when planning treatment.

Corticosteroids and immunotherapy in lung cancer present a unique challenge. While corticosteroids help manage symptoms, they can also affect how well immunotherapy works. This balance makes it important for doctors to personalize each patient’s care plan.

Impact on Treatment Outcomes

Tumor Response

Doctors use immunotherapy to help the immune system fight lung cancer. Tumor response measures how well the cancer shrinks or stops growing after treatment. When patients receive high-dose corticosteroids during immunotherapy, the chance of a strong tumor response drops.

Researchers have compared patients who took corticosteroids before or during immunotherapy with those who did not. The results show a clear difference in objective response rates (ORR):

Patient Group | Objective Response Rate (ORR) |

|---|---|

Steroid-exposed (within 30 days before ICI start) | |

Steroid-naïve (no steroids before ICI) | 36.7% |

Patients who did not take corticosteroids before starting immunotherapy had a much higher ORR. This means their tumors were more likely to shrink or stop growing. In contrast, those who took corticosteroids had a lower chance of a positive tumor response.

The dose of corticosteroids also matters. High-dose corticosteroids (more than 30 mg prednisone equivalent daily) lead to much worse outcomes. Patients on high doses have a lower chance of tumor control compared to those on medium or no steroids. Medium doses (more than 7.5 mg but less than or equal to 30 mg) do not show a significant difference from no steroids.

Note: Doctors sometimes prescribe corticosteroids for reasons not related to cancer, such as autoimmune diseases or lung problems. Studies show that when used for these non-cancer reasons and at typical doses, corticosteroids do not significantly affect tumor response rates. Problems mainly arise with high doses or when corticosteroids are used for cancer-related symptoms.

Patient Survival

Patient survival is another key outcome in cancer treatment. It tells how long patients live after starting therapy. High-dose corticosteroids can shorten survival for patients receiving immunotherapy for lung cancer.

A large review of studies involving over 5,000 patients found that those who received high-dose corticosteroids had a much higher risk of dying sooner. The hazard ratio for overall survival was 1.82, which means patients on corticosteroids were almost twice as likely to die compared to those not on corticosteroids. Progression-free survival, which measures how long patients live without the cancer getting worse, was also poorer with corticosteroid use.

Steroid Dose Group | Impact on Progression-Free Survival (PFS) | Impact on Overall Survival (OS) |

|---|---|---|

High-dose (>30 mg prednisone equivalent daily) | Markedly worse PFS (HRs ~3.2 to 6.0) | Markedly worse OS (HRs ~3.7 to 11.1) |

Medium-dose (>7.5 mg to ≤30 mg) | No significant difference from no steroids | No significant difference from no steroids |

No steroids | Baseline | Baseline |

Doctors also found that patients who stopped corticosteroids before starting immunotherapy had better survival than those who continued. This suggests that ongoing high-dose corticosteroid use during immunotherapy is especially harmful.

💡 Tip: For patients with non-small cell lung cancer, doctors should carefully weigh the risks and benefits before prescribing high-dose corticosteroids during immunotherapy. Lower doses for non-cancer reasons appear safe, but high doses can reduce both tumor response and survival.

Corticosteroids and immunotherapy in lung cancer require careful management. Doctors must balance symptom relief with the risk of lowering treatment success. By personalizing corticosteroid use, they can help patients achieve better outcomes.

T-Cell Maturation

Steroid Effects on T-Cells

Corticosteroids have a powerful impact on T-cell development and function. These drugs can change how T-cells grow, mature, and respond to cancer. When patients receive corticosteroids, several important changes occur in their immune system:

Dexamethasone, a common corticosteroid, blocks T-cell activities such as cytokine production and cell growth. This effect remains even when doctors use immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Prednisone, another corticosteroid, affects T-cells based on the dose. Low doses do not harm T-cell growth, but high doses reduce the production of IL-2, a key signal for T-cell development.

Both dexamethasone and prednisone increase the number of molecules like PD-1 and CTLA-4 on T-cells. These molecules act as brakes, slowing down the immune response.

Corticosteroids change the balance of T-cell types. They increase regulatory T cells, which calm the immune system, and reduce the number of active T-cells that fight cancer.

These drugs also lower the number of naïve T-cells, which are needed to recognize new threats, including cancer cells.

Note: The effects of corticosteroids on T-cells can depend on the type of steroid, the dose, and when doctors give the drug during treatment. Some effects are quick but can reverse after stopping the medication.

Immune Response Consequences

The changes in T-cell maturation caused by corticosteroids have serious consequences for patients receiving immunotherapy. T-cells play a central role in attacking cancer cells. When corticosteroids disrupt their development, the immune system loses strength.

Corticosteroids block signals through the IL-2 receptor. This action stops T-cells from multiplying and maturing.

The number of memory CD8+ T-cells drops. These cells help the body remember and attack cancer if it returns.

PD-1 levels rise on T-cells, making them less active and more likely to become exhausted.

Regulatory T cells expand, which further suppresses the immune response against tumors.

The overall effect is a weaker immune attack on cancer, making immunotherapy less effective.

Doctors treating corticosteroids and immunotherapy in lung cancer must understand these risks. By knowing how steroids affect T-cell maturation, they can make better choices about when and how to use these drugs. Careful management helps protect the patient’s immune response and improves the chances of successful cancer treatment.

Biomarker Monitoring

What Are Biomarkers

Biomarkers help doctors track how well cancer treatments work. In non-small cell lung cancer, two main biomarkers stand out: PD-L1 expression and tumor mutational burden (TMB). PD-L1 is a protein found on the surface of some cancer cells. Doctors measure PD-L1 using a test called immunohistochemistry. They look at the tumor proportion score (TPS), which shows the percentage of cancer cells with PD-L1. When the TPS is 50% or higher, patients often respond better to immunotherapy. Because of this, PD-L1 is the main biomarker used in clinics to guide treatment choices.

TMB tells how many changes, or mutations, exist in the tumor’s DNA. A high TMB means the immune system may find it easier to spot and attack cancer cells. Doctors use TMB to predict if a patient might benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors. Both PD-L1 and TMB help doctors decide which patients should get immunotherapy and how likely they are to respond.

Note: Not every patient with high PD-L1 or TMB will respond to treatment. Some may even have side effects or see their cancer grow faster. Researchers continue to search for new biomarkers to improve predictions and patient care.

Steroid Interference

Corticosteroids can make it harder for doctors to use biomarkers to monitor cancer. These drugs lower inflammation, but they also change the levels of proteins and signals in the blood. When patients take high-dose corticosteroids, PD-L1 expression may drop. This change can lead to a false reading, making it seem like a patient will not respond to immunotherapy.

Steroids can also affect TMB results. By suppressing the immune system, corticosteroids may hide signs that the body is fighting cancer. This interference can confuse doctors and make it difficult to adjust treatment plans.

PD-L1 levels may decrease after steroid use, leading to underestimation of immunotherapy benefit.

TMB readings may not reflect the true activity of the immune system during steroid treatment.

Doctors must consider these effects when monitoring patients. They often repeat tests or use extra caution when interpreting biomarker results in patients who need corticosteroids. Careful monitoring helps ensure that each patient receives the best possible care.

Evidence and Studies

Patient Data

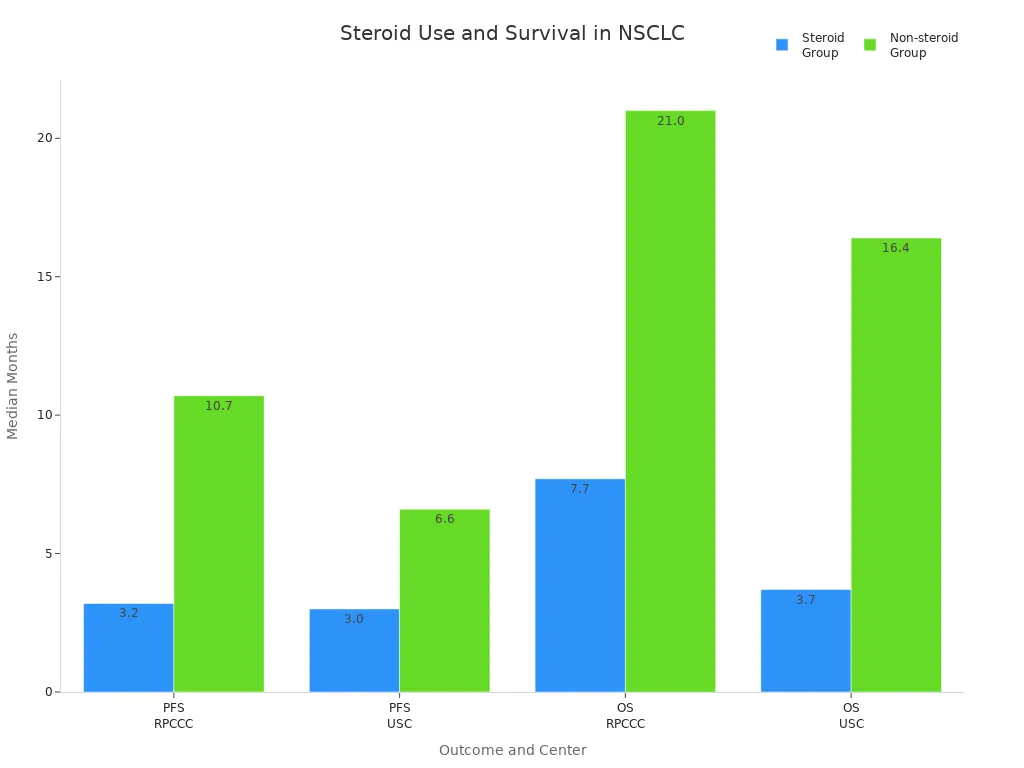

Researchers have closely examined how corticosteroids affect patients with non-small cell lung cancer who receive immunotherapy. In a large retrospective study, scientists looked at 277 patients treated at two medical centers. They found that patients who took high-dose corticosteroids before starting immune checkpoint inhibitors had much worse outcomes. These patients showed less tumor shrinkage and shorter periods without cancer growth.

Evidence Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

Patient Cohort | 277 NSCLC patients at two centers |

Steroid Use | 21 patients on baseline high-dose steroids |

Tumor Response | Less tumor shrinkage in steroid users |

Progression-Free Survival (PFS) | Steroid group: 3.0–3.2 months; Non-steroid group: 6.6–10.7 months |

Overall Survival (OS) | Steroid group: 3.7–7.7 months; Non-steroid group: 16.4–21.0 months |

Independent Risk Factor | Steroid use was the only significant risk factor for disease progression and death |

Immunological Biomarker | Lower CX3CR1+CD8+ T cells in steroid users |

Doctors also noticed that patients on corticosteroids had fewer mature T cells in their blood. This finding suggests that steroids weaken the immune system’s ability to fight cancer. The study confirmed that corticosteroids and immunotherapy in lung cancer require careful planning. High-dose steroids can lower the chance of successful treatment.

Animal Models

Scientists have used animal models to better understand how corticosteroids change the immune response during cancer treatment. In mouse studies, high doses of dexamethasone reduced the number of T cells and natural killer cells. These cells are important for attacking tumors. When mice received both corticosteroids and immunotherapy, their tumors responded less to treatment. Complete response rates dropped from 50% to as low as 0% depending on the steroid dose and timing.

Dexamethasone lowered CD4+, CD8+, and regulatory T cells in mice.

Tumors in mice treated with both steroids and immunotherapy grew faster and did not shrink as much.

In some brain tumor models, steroids did not block the benefits of immunotherapy, showing that tumor location matters.

In dogs, corticosteroids weakened both adaptive and innate immunity, making it harder for the body to remember and attack cancer cells.

These animal studies match what doctors see in patients. High-dose corticosteroids can block the immune system’s ability to fight cancer, especially outside the brain. The timing, dose, and reason for steroid use all play a role in treatment success.

Clinical Implications

Personalizing Steroid Use

Oncologists face important decisions when prescribing corticosteroids for lung cancer patients receiving immunotherapy. They must balance the benefits of symptom control with the risks of weakening the immune response. Corticosteroids serve many roles in cancer care, including managing immune-related side effects, controlling inflammation, and treating emergencies. Doctors often choose corticosteroids for their rapid action during oncological emergencies.

Corticosteroids help manage immune-related adverse events (irAEs) caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Systemic corticosteroids, such as oral or intravenous forms, work best for severe symptoms.

Local corticosteroids treat mild or moderate inflammation with fewer effects on the whole body.

Prednisone is often preferred for long-term use because it has better bioavailability.

Before starting corticosteroids, doctors check for active infections to reduce the risk of complications.

Prolonged corticosteroid therapy requires infection prevention and regular patient monitoring.

Doctors must consider the reason for corticosteroid use, the type of steroid, and the route of administration. In the adjuvant setting, corticosteroids may reduce immunotherapy effectiveness, so careful evaluation is essential. Personalization means weighing the benefits of symptom relief against the risks of immunosuppression and infection.

Oncologist Strategies

Oncologists use several strategies to minimize the negative impact of corticosteroids on immunotherapy outcomes. They focus on clinical judgment rather than routine avoidance of these drugs. The main concern often relates to the patient’s underlying disease rather than corticosteroid use itself.

Doctors prescribe corticosteroids for non-cancer reasons, such as autoimmune flares or COPD, without significant harm to immunotherapy results.

Aggressive reduction or avoidance of corticosteroids is not always necessary and may not improve outcomes.

Sensible prescribing ensures patients receive the right dose for the right reason.

Oncologists monitor patients closely and adjust treatment plans as needed.

Most commonly used doses for non-cancer indications appear safe during immunotherapy.

Tip: Appropriate corticosteroid use, guided by careful clinical assessment, helps maintain both symptom control and effective cancer treatment. Sensible decisions support better outcomes for lung cancer patients receiving immunotherapy.

Future Directions

Research Needs

Researchers continue to search for ways to reduce the negative effects of corticosteroids during immunotherapy. Many new approaches focus on minimizing the use of corticosteroids or finding safer alternatives. Recent clinical trials show that dexamethasone-free antiemetic regimens, such as those using olanzapine, palonosetron, or fosaprepitant, work as well as or better than regimens with dexamethasone for preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Updated guidelines now recommend limiting dexamethasone to a single day when possible.

Doctors explore the lowest effective dose and shortest duration for corticosteroid use.

Alternative antiemetic agents, like 5-HT3 and neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists, offer less immunosuppression.

Non-drug options, including behavioral therapies, music therapy, and dietary changes, help reduce the need for corticosteroids.

Future studies plan to test different steroid doses and measure serum cortisol levels to identify which patients benefit most.

Researchers highlight the challenge of balancing symptom control with the risk of weakening the immune system. Ongoing trials aim to find the safest ways to manage side effects without harming immunotherapy success.

Improving Outcomes

Doctors and scientists look for new strategies to help lung cancer patients who need corticosteroids during immunotherapy. They focus on overcoming immune resistance and supporting T-cell function.

Modifying the tumor microenvironment may help the immune system fight cancer even when corticosteroids are needed.

Enhancing T-cell activity could counteract the suppressive effects of steroids.

New immunotherapies, such as CAR T-cell therapy, may work better for patients who require steroids.

Combination treatments and biomarker-driven approaches allow doctors to adjust therapy based on each patient’s needs.

Personalized immunotherapy uses information from biomarkers like PD-L1 and genetic mutations to guide treatment choices. AI and machine learning tools analyze patient data to predict responses and manage side effects. By monitoring biomarkers and adjusting treatment, doctors can help patients get the most benefit from immunotherapy, even when corticosteroids are necessary.

The future of lung cancer care will rely on tailored strategies, advanced technology, and ongoing research to ensure every patient receives the best possible outcome.

High-dose corticosteroids can weaken immunotherapy for lung cancer by blocking T-cell maturation and interfering with biomarker monitoring. Studies show that these drugs not only reduce treatment effectiveness but also raise the risk of serious infections. Oncologists should personalize steroid use and consider alternative symptom management when possible. Ongoing research and strong collaboration between patients and doctors remain essential.

Careful decision-making helps protect both patient safety and treatment success.

FAQ

What are corticosteroids, and why do doctors use them in lung cancer?

Doctors use corticosteroids to reduce inflammation and control symptoms like pain or swelling. These drugs help patients feel better during cancer treatment. They also treat side effects from immunotherapy, such as rashes or breathing problems.

Can patients stop corticosteroids before starting immunotherapy?

Doctors may lower or stop corticosteroids before immunotherapy if possible. This approach helps the immune system work better. Each patient needs a personalized plan based on symptoms and medical needs.

Do all doses of corticosteroids affect immunotherapy the same way?

No. High doses weaken the immune response and lower treatment success. Medium or low doses, especially for non-cancer reasons, usually do not harm immunotherapy results.

Tip: Always follow the doctor’s advice about steroid dosing.

How do corticosteroids interfere with cancer biomarker tests?

Corticosteroids can lower levels of important biomarkers like PD-L1. This change may give false results on tests. Doctors may repeat tests or use extra caution when interpreting results for patients on steroids.

Are there alternatives to corticosteroids for symptom management?

Yes. Doctors may use other medicines, physical therapy, or lifestyle changes to manage symptoms. These options help reduce the need for high-dose steroids and support better treatment outcomes.

See Also

Key Facts About Symptoms Of Adrenocortical Carcinoma

Insights Into Large Cell Lung Cancer With Rhabdoid Features

A Guide To Symptoms And Treatment Of Adrenocortical Adenoma

Exploring Large-Cell Lung Carcinoma And Its Classification Types