Malignant Paraganglioma Explained: How It Differs from Benign Paraganglioma

When you ask what is malignant paraganglioma, you learn it is a rare tumor that can invade nearby tissues or spread to other parts of your body. ℹ️ Learn more in our Complete List of Cancer Types. Most paragangliomas are benign and do not spread. You need to know the difference because it affects your care and future. The table below shows how uncommon malignant cases are worldwide:

Tumor Type | Percentage of All Paragangliomas | Malignancy Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

Benign Paragangliomas | Approximately 90% of all cases | N/A |

All Paragangliomas | N/A |

Early detection helps doctors treat the tumor before it grows or spreads. If you have concerns, talk to your healthcare provider as soon as possible.

Key Takeaways

Malignant paragangliomas are rare tumors that can spread to other parts of the body, unlike benign ones that usually stay in one place.

Doctors confirm malignancy only when tumor cells appear in places where they do not normally belong, making diagnosis challenging.

Genetic mutations, especially in the SDHB gene, increase the risk of malignant paraganglioma and affect treatment plans.

Early diagnosis and a team approach to treatment improve outcomes and quality of life for people with paraganglioma.

Regular and lifelong follow-up is essential to catch tumor recurrence or spread early, even after successful treatment.

What Is Malignant Paraganglioma

Definition

You may wonder what is malignant paraganglioma and how it develops. Paraganglioma is a rare type of neuroendocrine tumor. These tumors grow from cells called paraganglia, which are found throughout your body. Most often, you find these tumors in the head, neck, chest, or abdomen. The most common sites include the carotid body in the neck and the adrenal glands in the abdomen.

Malignant paraganglioma means the tumor has the ability to invade nearby tissues or spread (metastasize) to other parts of your body. Doctors call this process metastasis. You may see these tumors in places where paraganglia do not normally exist, such as bones, liver, or lungs. This spread is the only absolute sign that a paraganglioma is malignant.

Note: Paragangliomas can appear almost anywhere in your body except the brain and bones. The most common locations are the head and neck, especially the carotid body, and the abdomen along the sympathetic chain.

Benign vs. Malignant

When you ask what is malignant paraganglioma, you also need to know how it differs from benign paraganglioma. Most paragangliomas are benign, which means they do not invade nearby tissues or spread to distant organs. Benign tumors usually stay in one place and grow slowly. Malignant paragangliomas, on the other hand, can invade blood vessels, nerves, or other organs. They may also return after treatment.

Doctors face challenges when trying to tell if a paraganglioma is benign or malignant. No single test or marker can always give a clear answer. The only sure way to diagnose malignancy is to find tumor cells in places where paraganglia are not normally found. Other features, such as tumor size, necrosis (dead tissue), and certain genetic mutations, can suggest a higher risk but do not confirm malignancy.

Here is a table that shows some of the main criteria doctors use to tell the difference:

Feature | Description / Criterion | Significance / Score |

|---|---|---|

Metastatic spread | Tumor cells found in distant organs | Malignant if present |

Tumor necrosis | Areas of dead tumor tissue | Score 5 |

Immunohistochemical markers | Loss of SDHB or S100 protein | Score 1-2 |

Vascular invasion | Tumor grows into blood vessels | Score 1 |

Tumor size | Larger than 7 cm | Score 1 |

A high score on these features means a higher risk of malignancy.

Doctors also use special scoring systems, like PASS or COPPS, to help decide if a tumor is likely to behave in a malignant way. However, these scores are not perfect. They help guide decisions, but only the presence of metastasis confirms malignancy.

Histological and Clinical Features

When you look at the tumor under a microscope, malignant paraganglioma may show:

Tumor cells invading blood vessels or the capsule around the tumor

Areas of dead tissue (necrosis)

High numbers of dividing cells (mitotic figures)

Tumor cells that all look very similar (cellular monotony)

Unusual shapes or sizes of cell nuclei (nuclear pleomorphism)

Loss of certain proteins, like S100 or SDHB, on special stains

Tip: Doctors often use a combination of these features, along with imaging and genetic tests, to make the best diagnosis.

Prevalence and Diagnostic Challenges

Most paragangliomas are benign. Only about 6% to 19% show malignant behavior, which means they spread to other parts of your body. The World Health Organization now considers all paragangliomas to have some risk of becoming malignant, so doctors recommend close follow-up for everyone.

Doctors cannot always rely on lab tests or tissue samples alone to tell if a tumor is malignant. The diagnosis often depends on finding tumor cells in places where they do not belong. This makes it hard to predict how a tumor will behave just by looking at it.

Genetic Factors and Relation to Pheochromocytoma

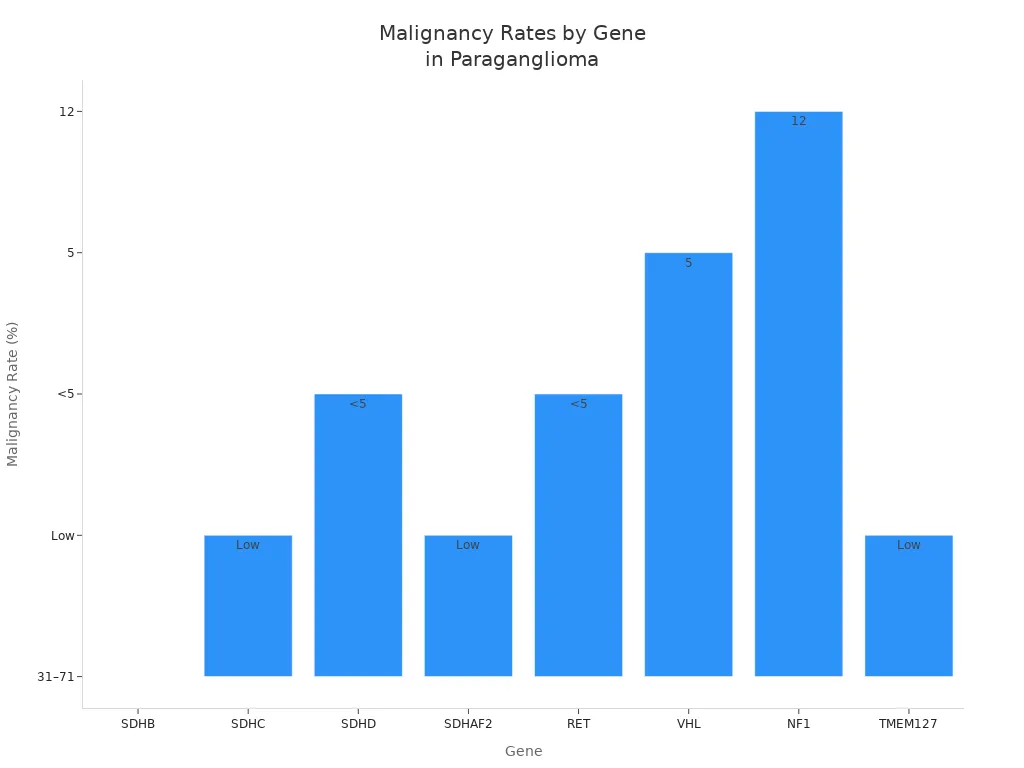

You may also ask what is malignant paraganglioma in terms of genetics. Certain gene mutations can increase your risk. The SDHB gene is the most important. If you have a mutation in SDHB, your risk of developing a malignant paraganglioma is much higher—up to 71%. Other genes, like SDHA, SDHC, SDHD, VHL, RET, and NF1, also play a role, but the risk is lower.

Paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas share many genetic and clinical features. Both tumors come from similar cells and can have the same gene mutations. Doctors often group them together as PPGL (pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma) because of these similarities. Genetic testing helps you and your doctor understand your risk and plan your care.

Note: If you have a family history of paraganglioma or pheochromocytoma, or if you are diagnosed at a young age, genetic testing is very important.

Key Differences

Tumor Behavior

You may notice that malignant and benign paragangliomas act very differently in your body. Malignant paragangliomas can invade nearby tissues and spread to distant organs. Benign paragangliomas usually stay in one place and do not spread. The table below shows how these two types behave:

Feature | Malignant Paraganglioma (MPPG) | Benign Paraganglioma |

|---|---|---|

Metastatic Behavior | Often spreads to lymph nodes, bone, liver, lungs; can reach rare sites like brain or skin | Rarely spreads (<10%) |

Location & Secretory Profile | Usually found in chest, abdomen, pelvis; often makes stress hormones (catecholamines) | Often found in head and neck; usually does not make hormones |

Metastatic Rate | Up to 70% in some types | Less than 10% |

Genetic Predisposition | Often linked to SDHB gene mutations | Linked to other gene mutations, but less likely to spread |

Histological/Molecular Markers | No reliable test to tell apart; only spread proves malignancy | Same as malignant |

Clinical Course | Can be slow or very aggressive | Usually slow and non-invasive |

Treatment | Focuses on controlling symptoms and slowing growth | Surgery often cures the tumor |

Note: Doctors cannot always tell if a tumor is malignant just by looking at it under a microscope. Only the spread to other parts of your body confirms malignancy.

Symptoms

Both malignant and benign paragangliomas can cause similar symptoms. These symptoms often happen because the tumor makes extra hormones or presses on nearby tissues. You might notice:

Fast or pounding heartbeat (palpitations)

Headaches

Sweating or flushed skin

Shakiness or tremors

Anxiety or feeling very nervous

Trouble breathing

Neck swelling or fullness

Hoarseness or changes in your voice

Pain in the area of the tumor

Trouble swallowing

Hearing loss or ringing in the ears (if the tumor is in the head or neck)

Sometimes, you may not have any symptoms at all. Both types of tumors can cause these signs, so symptoms alone do not tell you if the tumor is malignant or benign.

Tip: If you notice any of these symptoms, especially if they are new or getting worse, talk to your doctor. Early diagnosis can help you get the right treatment.

Prognosis

Your outlook, or prognosis, depends on several factors. Most people with benign paraganglioma do very well after surgery. Malignant paraganglioma can be more serious, especially if it spreads to other organs. However, many people still live for years after diagnosis.

Some important factors that affect your prognosis include:

Factor | How It Affects Prognosis |

|---|---|

Larger tumors are more likely to spread and can shorten survival. | |

Tumor Location | Tumors in the chest or abdomen are more likely to be malignant than those in the head or neck. |

Tumor Type | Sympathetic paragangliomas (in the chest, abdomen, pelvis) have higher risk of spreading than others. |

Genetic Mutations | SDHB gene mutations increase the risk of malignancy and may lower survival rates. |

Surgical Outcomes | Improved surgery has lowered risks, but tumors near nerves can cause lasting problems. |

Head and neck paragangliomas usually grow slowly and rarely make hormones. Tumors in other places, like the abdomen or chest, often grow faster and can cause more symptoms because they make stress hormones. Even with malignant paraganglioma, many people have good survival rates, especially if doctors find and treat the tumor early.

Note: Your doctor will look at your tumor’s size, location, and genetic background to help predict your outlook and plan your care. Regular follow-up is important for everyone with paraganglioma.

Diagnosis

Tests

When you visit your doctor with symptoms or concerns, the diagnostic process for paraganglioma starts with a careful review of your medical history and a physical exam. Your doctor will ask about your symptoms, family history, and any changes in your health. Next, you will likely have blood and urine tests to check for extra hormones made by the tumor.

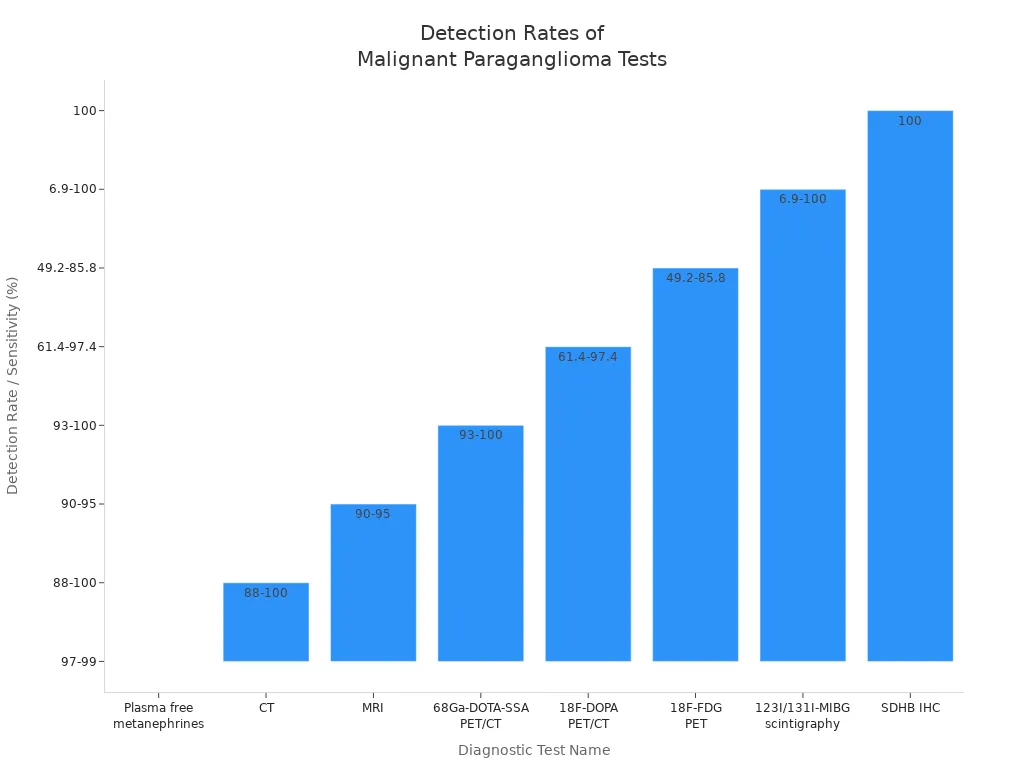

The most accurate blood test measures plasma free metanephrines. This test has a sensitivity of about 97–99% and a specificity of 89–94%. These numbers mean the test can find almost all cases and rarely gives a false positive. Doctors may also check for plasma or urine 3-methoxytyramine (3MT), which is especially helpful if you have a higher risk of malignancy, such as with SDHB gene mutations.

Diagnostic Test Type | Diagnostic Test Name | Detection Rate / Sensitivity Range (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

Biochemical Tests | Plasma free metanephrines | Sensitivity ~97-99, Specificity ~89-94 | Best for initial diagnosis of paraganglioma and pheochromocytoma. |

Biochemical Markers | Plasma/urine 3-methoxytyramine | Strongly associated with malignancy | Useful for screening and follow-up, especially in SDHB-mutated tumors. |

Pathological Assessment | SDHB Immunohistochemistry | Sensitivity 100%, Specificity 84% | Loss of SDHB protein suggests high risk of malignancy. |

Genetic Testing | SDHx mutation analysis | N/A | Identifies hereditary risk and guides prognosis. |

Doctors often use a combination of these tests to improve accuracy. No single test can always tell if your tumor is malignant. Only finding tumor cells in places where they do not belong confirms malignancy.

Tip: Genetic testing is important for everyone with paraganglioma, even if you have no family history. It helps find inherited risks and guides your care.

Imaging

After blood and urine tests, your doctor will use imaging to find the tumor and see if it has spread. CT scans are usually the first choice, especially for tumors in the abdomen or pelvis. MRI works well for tumors in the head and neck or if you cannot have a CT scan.

Functional imaging, like 68Ga-DOTA-SSA PET/CT, helps doctors see if the tumor has spread to other parts of your body. This scan has the highest detection rate for metastatic paraganglioma. Other scans, such as 18F-DOPA PET/CT or 18F-FDG PET, can also help, but they may not be as sensitive.

Doctors may also use a biopsy to look at the tumor under a microscope. They check for features like tumor size, cell growth rate (Ki-67 index), and loss of SDHB protein. These features help predict if the tumor might behave in a malignant way.

Note: Distinguishing between benign and malignant paraganglioma is difficult without clear evidence of spread. Regular follow-up and a team approach help ensure you get the best care.

Treatment

Benign Management

You have several effective options if you have a benign paraganglioma. Doctors often recommend surgery as the first step. Surgery can remove the tumor and control the disease in about 60% to 72% of cases. Sometimes, the tumor sits in a tricky spot or has many blood vessels, which makes surgery harder.

Radiation therapy is another strong choice. It works well for tumors in the bones or when surgery is risky. External beam radiation therapy uses doses between 30 and 50 Gy and controls the tumor in up to 100% of cases. Stereotactic radiosurgery is a newer method. It targets the tumor with high precision and uses lower doses, usually 12 to 18 Gy. This method works especially well for head and neck tumors.

You may need a team of doctors, including surgeons and radiation specialists, to plan your care. This team approach helps you get the best results with fewer side effects.

Malignant Management

Treating malignant paraganglioma often needs a combination of methods. Surgery remains the main treatment if doctors can remove the tumor. Sometimes, the tumor spreads or grows into nearby tissues, which makes surgery more difficult. In these cases, doctors may use surgery to remove as much tumor as possible and then add other treatments.

Purpose and Notes | |

|---|---|

Surgery | Removes tumor; best for localized disease; sometimes used for symptom relief |

Chemotherapy | Uses drugs like cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dacarbazine to slow tumor |

Radiation Therapy | Controls local tumors and relieves symptoms; doses often above 40 Gy |

Radionuclide Therapy | Delivers targeted radiation (e.g., 131I-MIBG, 177Lu); helps with widespread tumors |

Targeted Therapy | Uses drugs like sunitinib for certain cases; still under study |

Symptom Control | Medications manage hormone-related symptoms |

Doctors often combine these treatments to control the tumor and improve your quality of life. Most treatments aim to manage symptoms and slow the disease, as a cure is rare when the tumor has spread.

Follow-Up

You need regular follow-up after treatment for paraganglioma. Doctors recommend at least 10 years of check-ups, but lifelong follow-up is best, especially if you have a genetic risk or a large tumor. You will have blood or urine tests every year to check for hormone levels. Imaging, such as MRI, happens every 1 to 2 years for stable cases. If you have metastatic disease, doctors may check you every 4 to 6 months.

Recurrence can happen many years after treatment. About 6% to 17% of malignant paragangliomas return, sometimes even decades later. This long-term risk means you should keep up with your follow-up visits, even if you feel well.

Tip: Lifelong monitoring helps catch any new growth early, giving you the best chance for successful treatment.

When you ask what is malignant paraganglioma, you find that it acts more aggressively than benign tumors. Malignant paragangliomas often appear at a younger age, have higher recurrence and metastasis rates, and lead to lower survival. Early diagnosis and treatment tailored to your needs can improve your quality of life. You should always seek care from expert teams at specialized centers. For support, patient advocacy groups and organizations like the American Cancer Society and Pheo Para Alliance offer help with education, finances, and travel.

FAQ

What causes paraganglioma?

Doctors do not always know the exact cause. Some people inherit gene changes from their parents. These changes can increase your risk. Most cases happen by chance. You cannot prevent most paragangliomas.

Can children get paraganglioma?

Yes, children can develop paraganglioma. If you have a family history or certain gene mutations, your risk may be higher. Early testing and regular check-ups help find tumors sooner.

Is malignant paraganglioma curable?

You can sometimes cure malignant paraganglioma if doctors remove all the tumor before it spreads. If the tumor spreads, treatment focuses on controlling symptoms and slowing growth. Lifelong follow-up is important.

What should you do if you have a family history?

Tip: Tell your doctor about your family history. Genetic testing can help you understand your risk. Early screening and regular check-ups give you the best chance for early detection.

See Also

A Comprehensive Guide To Malignant Peripheral Nerve Tumors

An Overview Of Glioma And Its Various Types

Insights Into Bone Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma And Osteosarcoma

Essential Information About Ganglioneuroma You Must Understand

Exploring Glucagonoma And The Factors Behind Its Development